Is there a formal halachic obligation to act?

Contents

Introduction: Well, does it actually matter?

Conflicting halachic values

Halachic rulings require specific formulation

Identifying activities which halacha would certainly obligate/forbid

Tefillah (prayer)

Torah study/teaching

Not supporting unjustifiably harmful projects/policies (and supporting the opposite)

Introduction: Well, does it actually matter?

Before we deal with the question of whether there is a formal halachic obligation to deal with climate change, I want to first deal with the question of whether or not it matters. We have already demonstrated that there are several halachic values and principles which strongly indicate that Hashem would want us to doing something about the problem. Do we really need to say any more?

Nevertheless, I think there are a few reasons why it’s important to examine this question:

“It’s Torah and I need to study it” (Brachot 62a)

The most obvious reason is that halacha expresses the will of Hashem regarding how we should live and, paraphrasing the famous words of Rabbi Akiva above, our purpose in the world is to understand and live the will of Hashem.

Halachic obligations are taken more seriously

It is true that Judaism does not merely consist of a collection of laws. It possesses an underlying hashkafa (world-view) of values and principles defining defining how we look at the world, which includes those that we articulated. Nevertheless, when it comes to putting ideas into practice, there is no substitute for the power of a halachic imperative. If something is obligated or forbidden, it will be taken much more seriously.

This is evidently the case when it comes to the Torah world’s attitude to protecting the environment. Although the Torah’s values in this area are plain to see, when it comes to applying these principles in practice, very little is done. There are a lot of reasons for this, but it goes without saying that if people know that certain activities are convincingly shown to be obligated or forbidden by halacha, more will be done.

Need to understand the complexities of the issue

Over and above the question of whether Hashem wants us to deal with climate change is the question of what we should be doing about it. In order to do that, it is not sufficient to merely highlight values that support action, but one must also examine how these principles should be applied in reality and what different considerations need to be taken into account. For this, a halachic analysis is required.

With those thoughts in mind, let us now explore the issue.

The challenges involved

Although the principles raised would seem to forcefully demand dealing with climate change, expressing this in terms of formal halachic obligations raises some challenges.

1. Conflicting halachic values

Some halachic values might, at first glance, appear to demand extreme action in dealing climate change. However, there are conflicting values that need to be taken into account.

For example, let’s look at the preservation of human life (pikuach nefesh), which we highlighted as a major value relevant in dealing with climate change. As we stated, it is one of the highest halachic priorities. Even situations which are only potentially life-threatening (safek pikuach nefesh) will often justify violating Shabbat. The Torah’s obligation to remove hazards and prevent danger to society is very far-reaching, holding those who fail to intervene to have blood on their hands. From the law of egla arufa we learn that this is the case even if their intervention might not have made a difference. So you might conclude on that basis that we must fight climate change at all cost to avoid risk to human lives.

However, even in the area of pikuach nefesh, we see that the halacha also recognizes that the effective functioning of a society often entails its citizens being exposed to a certain amount of risk. For example, a person is allowed to undertake a risk-laden profession if it is necessary for them to make a living (as discussed by the Noda B’Yehuda). Similarly, once society has adopted a certain practice, even if it entails a certain degree of risk, one may trust that Hashem will protect them (Shomer p’sayim Hashem). This indicates that Hashem takes into account society’s need for stability. On a day-to-day basis, halacha doesn’t object to people driving cars, despite the risks and the death toll involved. At the end of the day, there is a certain threshold of risk, and an associated death toll, that is deemed to be acceptable.

Conflicts of values makes things complicated, although it does not, in and of itself, make halachic rulings impossible. Much of our Responsa literature seeks to provide guidance in the presence of conflicting values. But there’s a bigger problem.

2. Halachic rulings require specific formulation

What really becomes tricky with climate change is that, even after weighing up competing values and reaching a conclusion, how does one formulate that as a halachic ruling? Generally-speaking, halachic rulings mandate, permit or forbid specific activities, such as: whether one must vaccinate or not, whether one can eat certain foods or not, whether one can engage in certain business practices or not. But how would you implement something like that here?

For instance, if the conclusion was reached that it is halachically forbidden for humanity to emit the quantity of greenhouse gases that it is currently emitting, how would that translate into specific halachic instructions? Would that dictate that each individual or family and each corporation should be assigned a budget of permissible emissions over time tailored to their circumstances (assuming such a thing is possible)? That might make sense if the rest of society is essentially doing the same, because even though this would create a significant burden for the individuals concerned and might be significantly disruptive to their lifestyle, everyone is in this together and each individual’s action will make a significant difference to the problem as part of a collective solution. However, if the observant Jews are the only ones doing this, it would be difficult to say that they are obligated to undertake such a burden when it will not help the situation one bit.*

Furthermore, there are a lot of different approaches recommended for dealing with climate change. We just discussed individuals reducing their carbon footprint. Another is to take action politically or economically. Many recommend the importance of speaking about climate change with others in order to influence public opinion. Some of these activities seem really incompatible with being expressed as halachic obligations.

There are a bunch of other challenges we would also need to consider (see the footnote**), which we hope to discuss elsewhere. For the purposes of this article, we will limit our discussion to those above.

* Actually, renowned posek, Rav Osher Weiss shlita, concluded that any behavior which, if pursued by the entire society, would lead to a problematic outcome, is considered problematic and forbidden even for an individual, regardless of whether the rest of the society is refraining from that behavior or not. He derives this from the midrash which says that the generation of the flood (Dor Hamabul) was condemned by Hashem for their thievery, even though each individual stole less than the minimum value of currency (shaveh pruta). On this basis he argues that vaccination is obligatory for every individual and that no one can excuse themselves even if herd immunity has been achieved without them.

One might want to infer from this that in the situation that we are describing it would be forbidden for a Jew to exceed their personal carbon budget even when no one else is adhering to one. Nevertheless, it would seem that the situation we are describing here is different in a number of ways.

Most significantly, the obligation devolves upon the

individual only because there is an assumed legitimate

carbon budget for humanity as a whole. If, however,

humanity as a whole does not commit to adhering to such

a budget, there is no real basis upon which to obligate

individuals.

** In addition to the challenges raised above, there

are also a number of technical halachic questions

that require consideration, which are not our focus

here, such as:

- how to render a

halachic risk assessment of climate change, and

- whether individuals, whose personal contribution

to the problem is negligible, are responsible for the

damage that results from the collective effects of

their actions

- whether the

chain of causation between individuals' and the

impacts of climate change is proximate enough to

generate halachic obligations.

- what if our remedial actions are inconsequential to

solving the problem? Would we still be obligated?

I hope to address these issues in future articles. For

now, we will assume that these considerations do not

limit our responsibility to act against climate

change.

Responses to these challenges

Despite all of this, we will now see that there are still a number of ways to formulate halachic obligations in response to climate change.

1. A collective duty to respond

In response to the above, we have to realize a couple of points:

Not all halachic obligations are expressed as specific actions to perform

Some call upon us to respond to particular circumstances that arise as required. For example, we are required to perform gemilut chasadim (acts of kindness) to help those who are in need. What does one need to do? Whatever needs to be done, or at least whatever one is capable of doing.

Some needs demand more of a collective response than an individual one

When the Jewish people identify a major, large-scale problem that can only be effectively tackled collectively, then the obligation of gemilut chasadim demands that we do so. For example, when Jews in the Soviet Union were being persecuted for wanting to leave for Israel from the 1960s to the 1980s (“Refuseniks”), there was a halachic and moral need for the Jewish people around the world to try and solve the problem. The result was worldwide Jewish activism which ultimately succeeded in getting them out.

When it started to become clear how many Jews were being lost to assimilation and intermarriage, there arose a halachic and moral obligation for Torah Jewry to seek to address the problem. In response to this awareness, various initiatives emerged from different quarters of the Jewish people, leading to the kiruv movement, which has had different levels of success since it began many decades ago.

It would seem clear that the threat of the magnitude of climate change creates a halachic imperative upon us to collectively confront the issue and consider how we should address it.

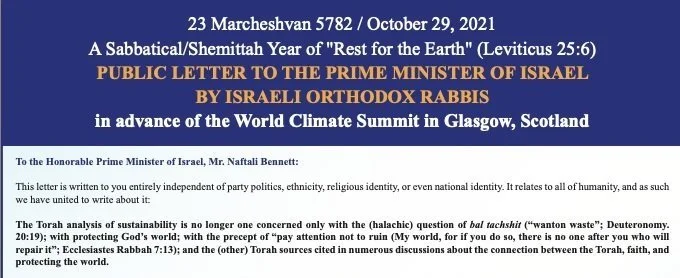

Along these lines, in October 2021, a group of leading Israeli Religious Zionist rabbis wrote an open letter to then-Prime Minister, Naftali Bennett, on the eve of his travelling to the Scotland to represent Israel at the World Climate Summit, stating that as Jews we are obligated to address climate change and urging him to enlist the State of Israel’s full participation in global efforts.

Open Letter from Leading Religious Zionist Rabbis to Former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett (translation)

Click here to see the full letter

2. Identifying activities which halacha would certainly obligate/forbid

Although it may be challenging to formulate certain activities as halachic obligations, such as reducing one’s carbon footprint or engaging in economic or political action, not all activities are so challenged:

a. Tefilla (prayer)

If halacha considers prayer an appropriate response to climate change, as we have suggested, it is not subject to the above challenges and should be obligatory. As Torah Jews, we believe that prayer is valuable, regardless of whether it is broadly adopted or not, and even if it is challenging to take on. While the appropriate format and frequency of such prayer would need to be formulated, it seems clear that we must turn to Hashem and daven for siyata diShmaya (Heavenly assistance).

b. Torah study/teaching

If this is indeed an area of service of Hashem that has been neglected, as I have suggested, then there would seem to be a halachic requirement to devote more attention to studying and teaching this area. In addition to this causing people to take this area of Torah more seriously, which is important in itself, it also has the power to cause knock-on affects which address climate change:

Influencing public opinion - Public option has a major effect on governmental climate policy, one of the most powerful tools with which to address climate change.

Inspiring Jewish initiative - Torah Jews have significant influence in many spheres and can potentially make a big impact in this area if they seek to apply themselves towards it.

c. Not supporting unjustifiably harmful projects/policies (and supporting the opposite)

As we’ve state above, there is a need to balance halachic values demanding action with those that seek to provide for society’s current and ongoing needs. Working out this balance might not be something that one can calculate using a mathematical formula, it may take some degree of intuition and guesswork. So when it comes to specific projects or policies, determining what is forbidden, permitted or obligatory would not be black-and-white. Nevertheless, there will be projects and policies whereby the values scale will be tipped overwhelmingly to one side and it is simply a no-brainer.

Let’s look at the state of the Amazon rainforest, for example. The Amazon is one of the world’s major carbon sinks, but deforestation, climate change and other causes threaten to irreversibly ruin it. Now, if you ask what considerations would halachically justify irreversible ruin to such an important global resource, with all of its resulting implications, it seems clear that they would have to be incredibly significant. What if they are not? Supposing, for argument’s sake, that the Amazon was being ruined in order to maintain and expand the global beef industry, this state of affairs would apparently have no halachic justification. For Jews to invest in, promote or support an industry or policies that are doing this would seem to be halachically forbidden (and one may be obligated to even oppose them).

At the other extreme, if there are policies and projects which would significantly help in tackling climate change which have little negative impact on people’s lifestyles, it would seem to be halachically obligatory to encourage them and forbidden to oppose them.

3. Establishing new halachic policies

The above responses seek to identify halachic obligations and prohibitions which already exist. However, we have a precedent of our Sages setting in place new halachic stipulations, in tension with the existing halacha, deemed necessary to manage society’s needs. The Gemara states:

The Sages taught in a baraita: Yehoshua (Joshua) stipulated ten conditions when he apportioned Eretz Yisrael among the tribes, that people shall have the right to:

1. graze their animals in forests, even on private property;

2. gather wood from each other’s fields, to be used as animal fodder;

3. gather wild vegetation for animal fodder in any place except for a field of fenugreek;

4. pluck off a shoot anywhere for propagation and planting, except for olive shoots;

5. take supplies of water from a spring on private property… (Bava Kama 80b-81a)

If Hashem never made such stipulations, how could Yehoshua have the chutzpa to do so? Apparently, Hashem never intended Biblical halacha to address every situation and need, and Hashem entrusts our Sages to use their discretion and implement principles for effective living as circumstances require.

Therefore, if our Torah leaders conclude that we have a national duty to respond to climate change (Response #1 above), they might consider simply elucidating existing halachic priniciples to be insufficient, and may consider it necessary to create new halachic restrictions, provided that this is done in a way in which communities are on board and are capable of implementing them.

So, although we argued above that there are significant limits as to what actions halacha can be said to forbid or obligate, that is only true with regard to existing halacha, but not with regard to halachic innovations. While it might be challenging to argue that there is an existing halachic obligation to reduce our carbon emissions as we suggested, it is conceivable that, given the right conditions, at some point our Torah leaders could impose halachic restrictions on carbon emissions.

This may sound unlikely, although interestingly one Chareidi writer has already argued in favor of a ruling limiting eating meat to Shabbos and Yom tov. While this suggestion seems unlikely to be taken up in the near future, the fact that it has even been suggested indicates that mindsets are starting to shift and that, in the right social climate, this could actually start to happen.

Summary

Although it is challenging to articulate halachic obligations or prohibitions addressing climate change:

There is value in doing so for several reasons, including that people take it more seriously.

It is still possible to articulate a broad halachic obligation to collectively confront the issue, which some leading rabbis have already done.

It is also possible to identify specific halachic obligations which do not face the discussed challenges, such as:

an obligation to support (and not negate) policies and projects which successfully address climate change which have no major downside for society.

a prohibition with regard to supporting policies and projects which unjustifiably exacerbate climate change.

an obligation to engage in tefilla (prayer) and more study of Torah related to our responsibilities to the environment.

At some point, under the right conditions, our Torah leaders may also consider it appropriate to innovate new halachic restrictions.